RYA Course 23’. Meteorology in the Southern Ocean

Vicious storms, or more formally mid-latitude depressions, are constantly born, moving almost unimpeded across the southern ocean. These low-pressure systems rotate clockwise in the southern hemisphere due to the action of the Coriolis force, named after the French mathematician, engineer, and scientist Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis.

His studies led him to conclude that an apparent force acts on atmospheric particles moving in a rotating frame of reference. As the atmosphere is attached to the surface by friction and gravity, its weather phenomena move in a rotating frame and thus experiment Coriolis force effects. Conspicuous spiraling cloud structures known as fronts appear in satellite images associated with low-pressure systems, as water vapor condenses when the air cools down as it is pushed upwards in the troposphere.

In the southern hemisphere, depressions meet few land masses as they travel across the oceans, especially at high latitudes, so winds blow fiercely, giving a proper name to the roaring forties and screaming fifties latitudes. If you have been sailing down there, you know this is true.

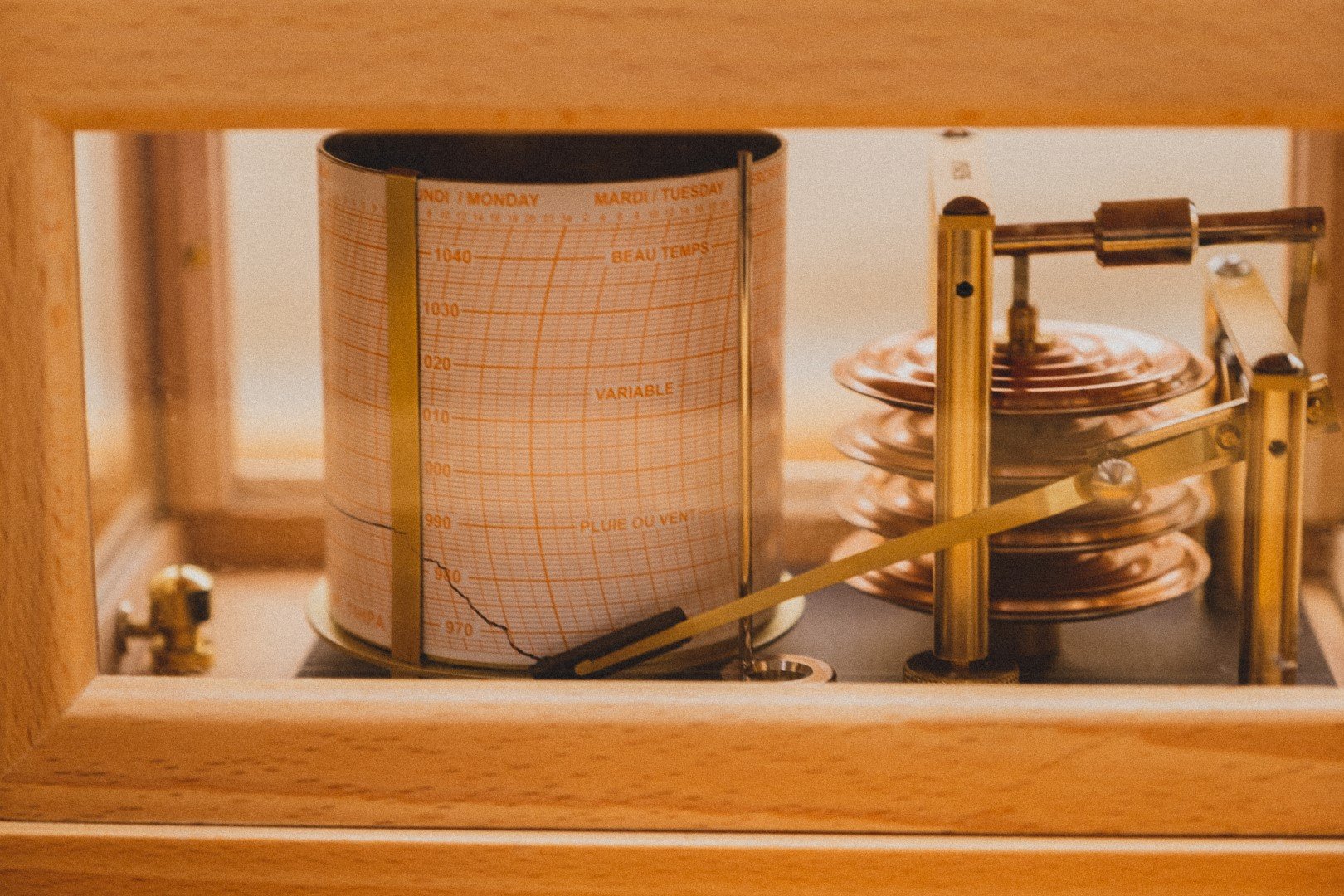

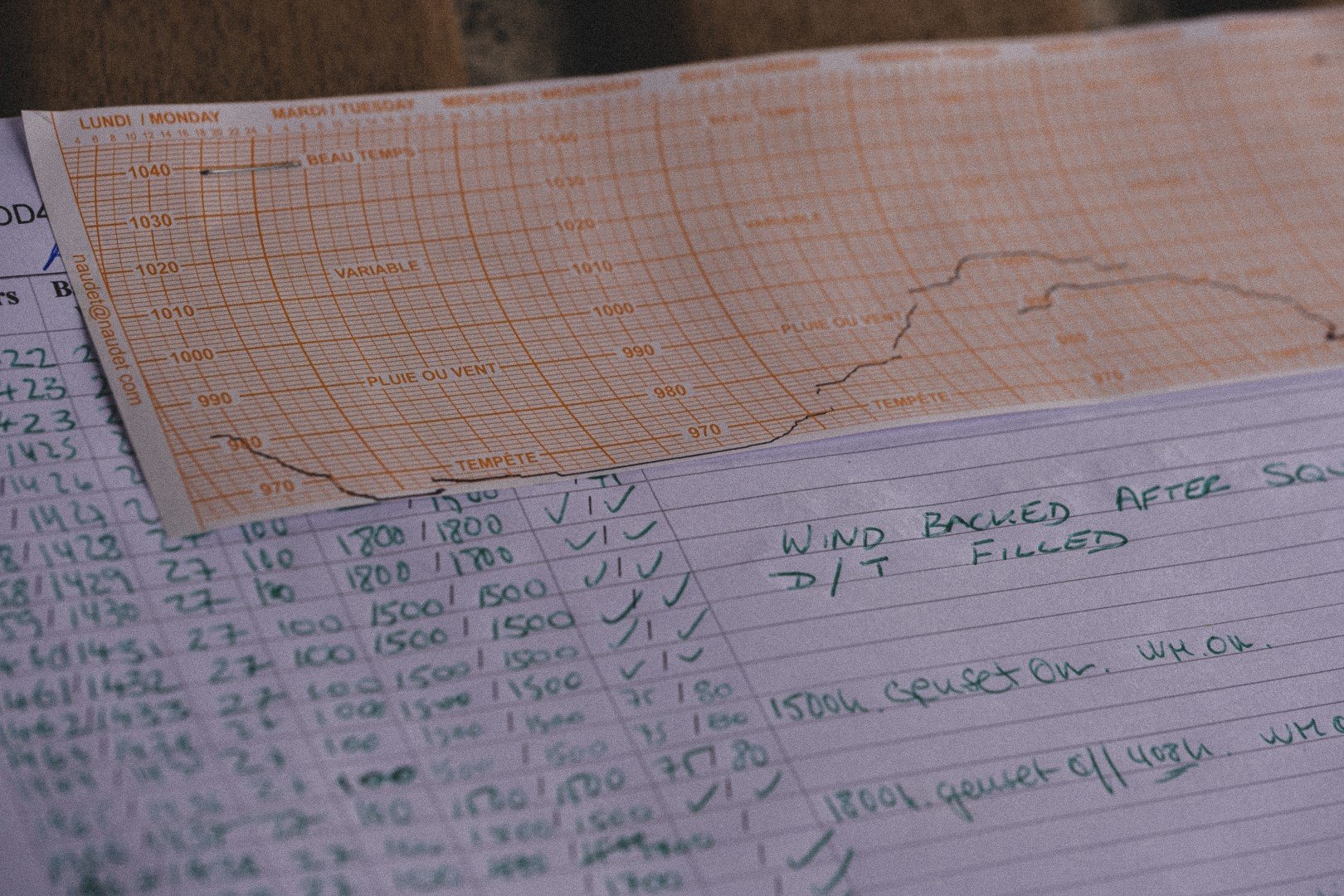

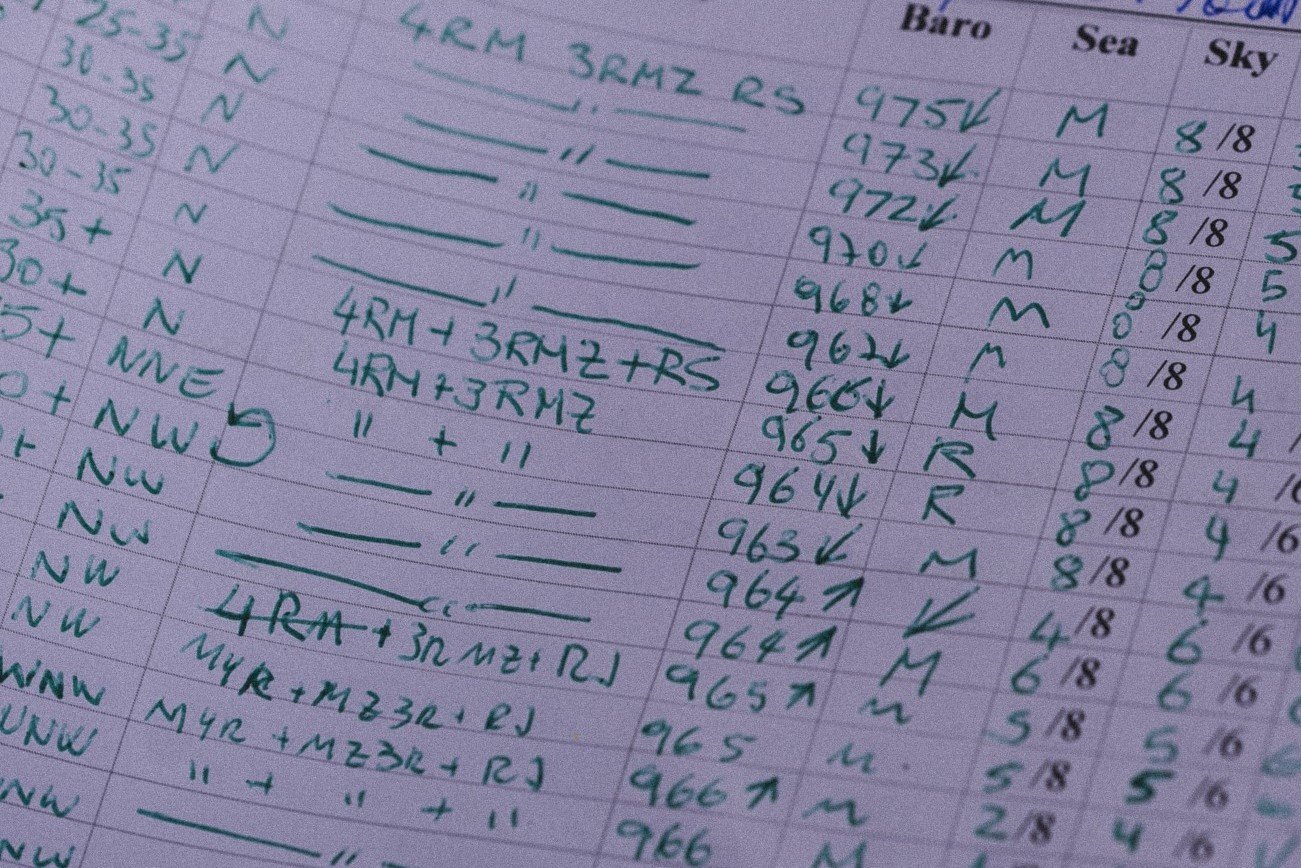

The wind starts to "scream" when its speed exceeds 45 or 50 knots as it interacts with the ship's rigging. But the wind also tells you its own story. The arrival of an intense depression is announced by a marked drop of the surface pressure we usually record on board with a barograph.

Generally, the steepest the down curve in the barograph, the stronger the winds will blow in the following hours. Furthermore, the sea state might get quite complicated in the core and surroundings of such depressions as background long period swell of 2 to 3 meters wave height often exists and interacts with the locally generated short period wind waves in the fetch or with a secondary swell coming from very different directions, creating instabilities which could end in huge waves breaking out to sea.

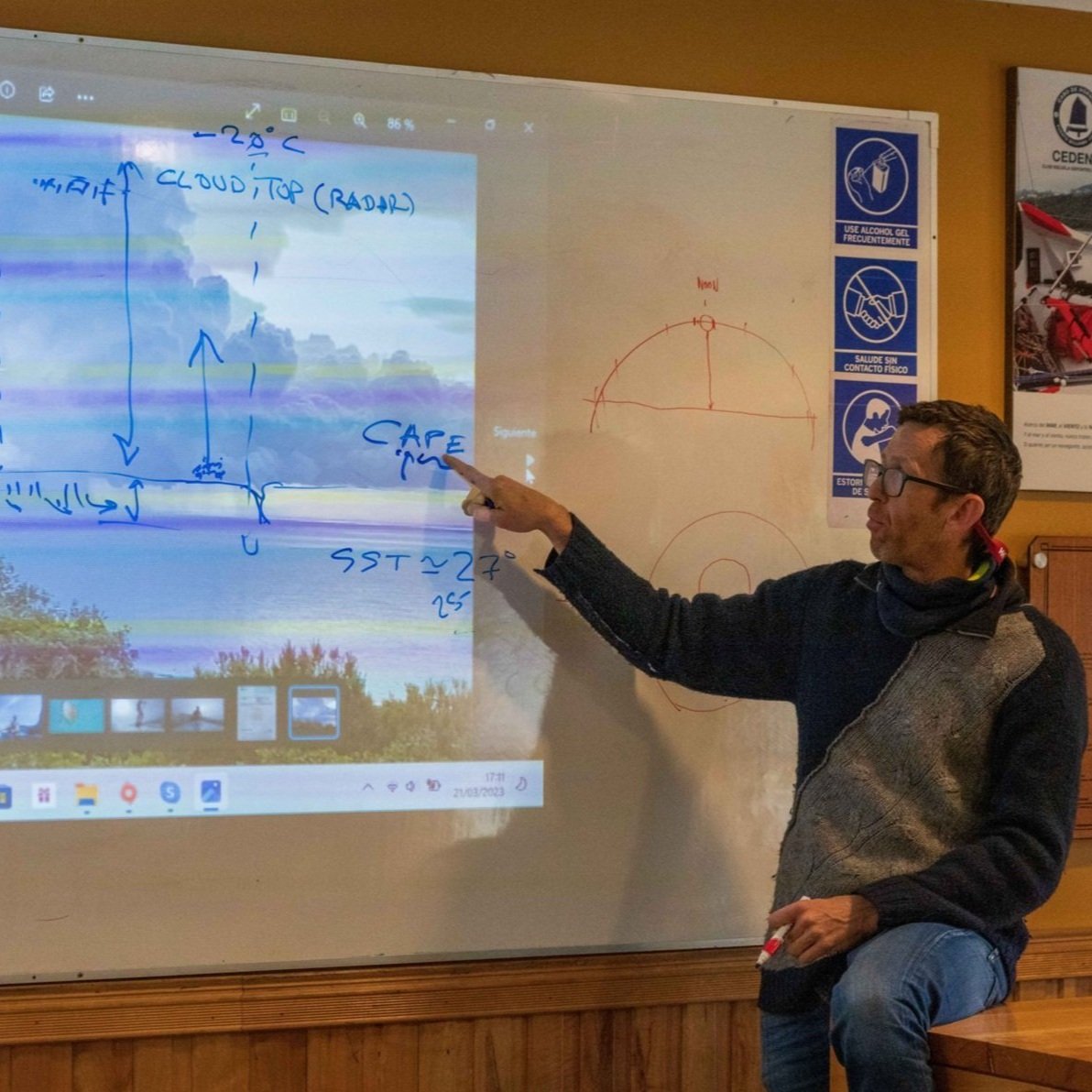

RYA Yachtmaster Ocean students have been analyzing these phenomena first on land and then experimenting with them directly while sailing. They have seen which clouds are typically observed in different areas around a depression and how average wind and gusts behave close to cold fronts. Of course, students also have some homework in the form of practical exercises, which will help them to become proficient in reading isobaric charts, doing long-distance passage planning based on meteorology, or learning how to apply the 1-2-3 mariner's rule for revolving tropical storms.

Then, the challenge here is to develop the awareness needed to relate weather forecasts from state-of-the-art numerical models arriving from satellites to observational data, some coming directly through our senses and others by measurement equipment on board.

Pictures by Kenneth Perdigón and Scott Gallyon

Gabi Pérez

Meteorologist