Creativity in continuous motion

A long passage across the South Atlantic is life in continuous motion. Even when our bodies are adapted, everything is physically moving. We cannot set something down for long before it slides across the surface. Hold on at all times. Time, too, becomes more circular than episodic. Awake or asleep at any time of day: 3 hours on watch, 6 hours off, 24/7. At first this felt like perpetual jetlag, and then it settled into a rhythm I found profoundly creative.

The quiet night watch. First stage: reluctance. Second stage: observing the pilot house clock move at half-speed, waiting for any action like the hourly logbook entry. Third stage: great excitement if there is a sail manoeuvre, otherwise muster the energy to occupy 1 or 2 hours while most of the boat is asleep. Get bored, start a project, put it down. Pick it back up during the day, work on it, talk about it, change direction, put it down. Creativity in continuous motion: anti stagnation.

Sewing, sketching, painting, muralling, cooking, baking, splicing, knot tying, suturing practice, sail patching, fixing broken things, phototography, poetry, bird watching, plotting dead reckoning, graphing sun sights, pages of calculations, inside jokes, playing guitar, playing chess, finding constellations, inventing new constellations, listening to and appreciating music, reading books, sharing stories, recounting history.

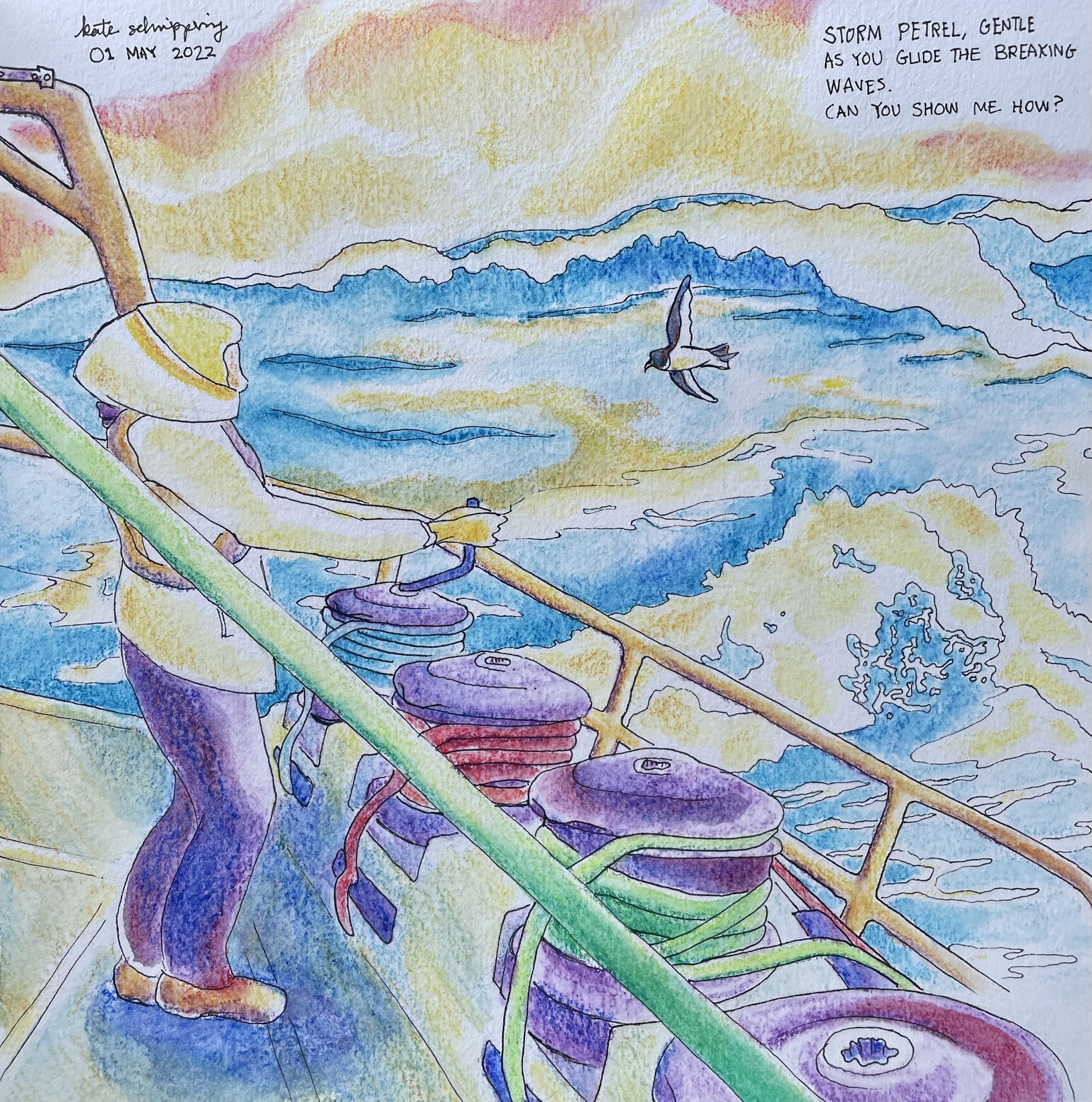

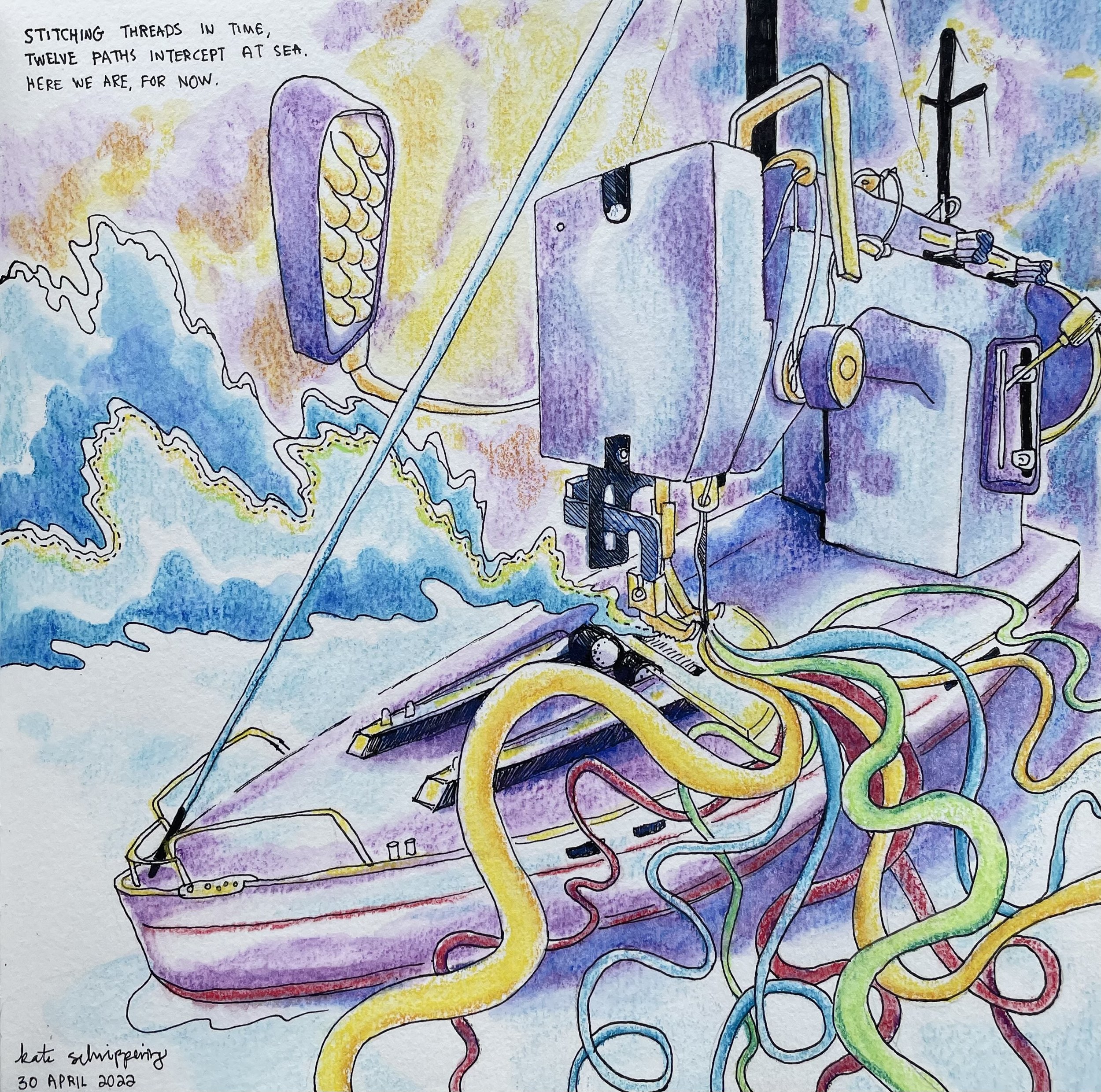

Sketching helped me process the experience as we were living it. Noticing more closely, and trying to capture the layers both real and metaphorically present.

Storm petrel, gentle

As you glide the breaking waves.

Can you show me how?

We are surrounded by birds most days of the passage. At times - hundreds of prions, or a dozen different species flocking together. They almost never land. Seabirds, too, are in continuous motion, grazing on the water. When the wind picks up, the tiniest of all of them - the storm petrel - daringly flies under the crests of breaking waves. What might be very exciting conditions for us (like 35-40kts of wind) are an inextricable part of who she is. She is our teacher: hold a gentle, focused presence - and so you can glide instead of crash in these waves.

On the passage, we each have opportunity to show up as a teacher and a student, regardless of our role on the team. I noticed the steadfast patience and calm of all of our teachers - especially as we students got to know the unfamiliar systems of Vinson and made plenty of mistakes. Standing on the platform of the mizzen mast at 2am in wind and rain: a perfect time to slow down and think through a new task together.

Stitching threads in time,

Twelve paths intercept at sea.

Here we are, for now.

I was incredibly excited to discover a Sailrite LSZ-1 sewing machine aboard, and the Skipper invited me to make a South Africa courtesy flag as we needed one to land in Cape Town. We had limited fabric on board - especially the green. I constructed it from an Echo code flag, Zeta code flag, Brazilian flag, and Portuguese flag. There were many small pieces to engineer together. I was reminded of Vinson’s four mainsail reefing lines of the same colours - red, blue, green, yellow - that must work in cooperation.

South African flag

While sewing the flag, I thought of our crew of 12 coming from different countries and backgrounds. As a sewing machine joins separate pieces of fabric - a “red-over-green sailing machine” (mnemonic for nav lights at night) joins and stitches our lives into this sea-cloth, into one story.

To take it one level deeper: in celestial navigation, we are calculating the circles projected by celestial objects onto earth, based on the angle and time of observation. If we are somewhere on circle A and somewhere on circle B, we must be in the position where they intersect. So a sewing-sailing machine fixes both our position in spacetime, and fixes the moment across our lives. Only here and now are we together, and soon we will be apart. By the time we know where we are, we are no longer there.

Wake up! Albatross,

Ride the wind, capture the sun,

Wander and be found.

Wake up, sleepy Dodo! You’re late for watch! When the sun no longer works as an alarm clock, our 15-year-old trainee requires no fewer than 17 alarms to get out of bed and on deck in oilskins.

With celestial navigation, we are constantly paying attention to the sun, and estimating the meridian pass - the sun’s highest point in the sky. The sun is always on our port side, declination north.

By capturing the sun with our sextants, we can know approximately where we are - latitude and longitude lines are our grid on the sea. They remind me of the swell, which comes and goes and changes direction with the winds.

We also ‘wake up’ to the lessons of the voyage. We learn that we can only approximately decide where we are going. The winds are pushing us away from Tristan da Cunha. There is no way to stop and wait it out. Heartbreak. For a brief tack we switch directions westward instead of eastward and our whole world feels upside down.

Our new trajectory takes us near to Gough Island. When we follow the sun and the wind, we are in a sense wandering - we end up somewhere other than where we thought we were going.

Despite mounting evidence that we might pass Gough in the night, fail to see it due to dense clouds, or miss it entirely if our calculations were far off, we did find the Island. Meticulous calculations and suspense for two foggy days since our last sun sight.

We wake up to Gough Island. The fog parts and the sun breaks through. It’s unbelievably stunning with verdant waterfalls pouring over cliffs: Atlantic Kauai. The researchers stationed there are elated to chat with us over the radio and invite us over for coffee (we know this to be impossible).

Wake up and learn from the Wandering Albatross - the largest of albatross who can spend years at sea and live to be over 50. Although you may not know where you are, trust in the elements and conditions to be your compass, and you will find your way.

Kate Schnippering.

Student, designer, sailor, adventurer