Navigator’s collective

Almanacs, pencils, paper charts, dividers. Sextants, planets, stars, the Sun. For the last two weeks, these have been the most used words and navigation equipment on board. We are teaching a celestial navigation course. A day after leaving Tierra del Fuego heading toward South Africa we blinded the GPS information from the electronics equipment. We kept using the Ais system and the radar for collision avoidance, but from a navigation perspective, we were back to just astronomical means.

Penguin Island and the eastern side clifts

Briefly explained, the old times method works as follows: First, you need to guess where you are. To do so, every hour we plot our estimated position. We draw a small line whose direction is the heading kept in the last hour, and its length is the distance sailed. By adding all these consecutive lines you end up with a presumption of where you are. But you may have overestimated your boat speed, mistaken the compass reading, or misjudged the ocean currents. That position is just a guess. After this very graphic exercise, comes the second part of the process. Taking a sextant reading from a celestial body –a planet, the sun, or a star- and a bit of maths, you will end up knowing how far you are from the estimated position. The astronomical part of the method corrects the lack of accuracy of the first part. It tells you where you really are.

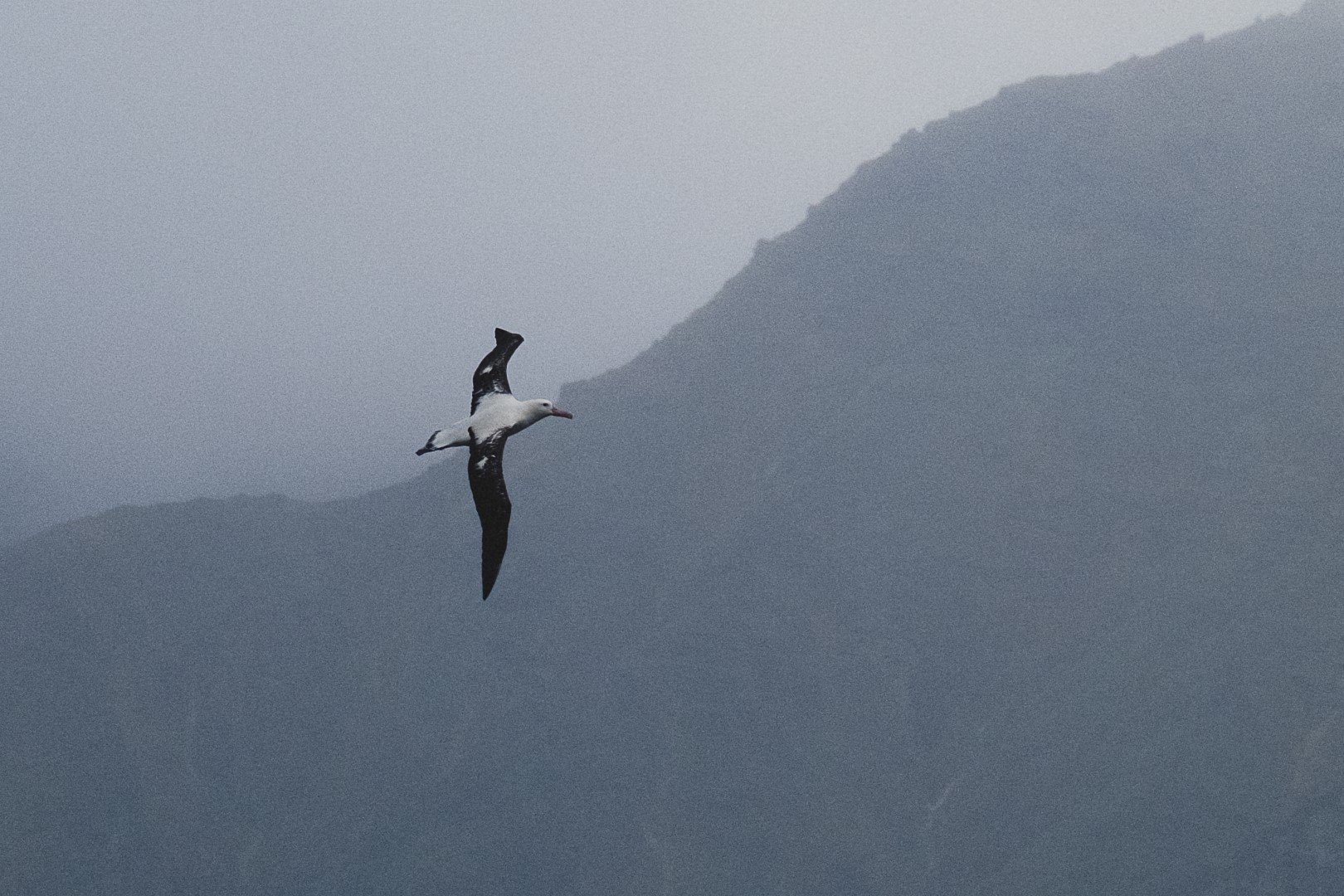

A Wandering Albatross sky-diving near Penguin Island

This is how navigators fixed their ship’s position at sea over the centuries. But this method had a strong and a very capricious enemy. To fix your position you need to see a celestial body. While you can accept good levels of uncertainty while in the open sea, precision becomes crucial when finally approaching land. Few will care if you are fifty miles off in the middle of the ocean, but you can miss a small island if, when you need an accurate position, you find yourself surrounded by a dull gray sky. Clouds are the navigator’s nightmare.

Since we left Patagonia we have been practicing and improving our celestial navigation skills. We had two weeks to refine our ability to the highest possible level. And just like that, you can aspire to find a small rock in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. But the sea gods were playing with us. Two days before reaching the island an overcast sky left us totally blind. The only hope we had of succeeding was dependent on extremely precise dead-reckoning navigation. The least lack of attention to currents, leeway, compass deviation, or magnetic variation calculations would send us miles off our destination. Through many watches, we noted the compass course every fifteen minutes. We were very demanding with each of our small line drawings. We had to be constantly and completely meticulous in everything we did.

Lots wife and Round Island in transit

Sooty Albatross, Southern Giant and Spectacled Petrels

The effort paid off, and at dawn, and still with no sun, we spotted the northern side of the island. Smiles, fulfillment, pleasure, and some relief. But I did have this thought: I’m sure some of the students dreamed about being the one taking that very last astronomical sight that would put us on the right path to Gough Island. As opposed to just one person’s success in finding the island, our achievement was entirely collective. Each person’s effort had the same value. None of us was greater than the rest, we all found the island together.

Dead-reckoning drawings

The place was astonishing, dramatic, and completely isolated. While sailing south along its eastern coast we were surrounded by very special sea birds. Sooty, Wandering and Tristan da Cunha Albatrosses, White Chinned, Spectacled, Northern Giant and Southern Giant Petrels, Prions and Little Shearwaters, Terns. All of them at once, simply mind-blowing.

Part of the crew posing in front of Gough Island

We knew there was a small group of researchers living there. When we were close to the only building we saw, we got to talk to them on the radio. They were an ornithologist party on an eleven months expedition. We waved to each other. For both us and them, we were the closest human presence for some time. And in that radio conversation, without really knowing about who we were, from the remotest inhabited archipelago on the planet, they asked if Skip was on board and sent him their regards.

Kenneth Perdigón

Skipper